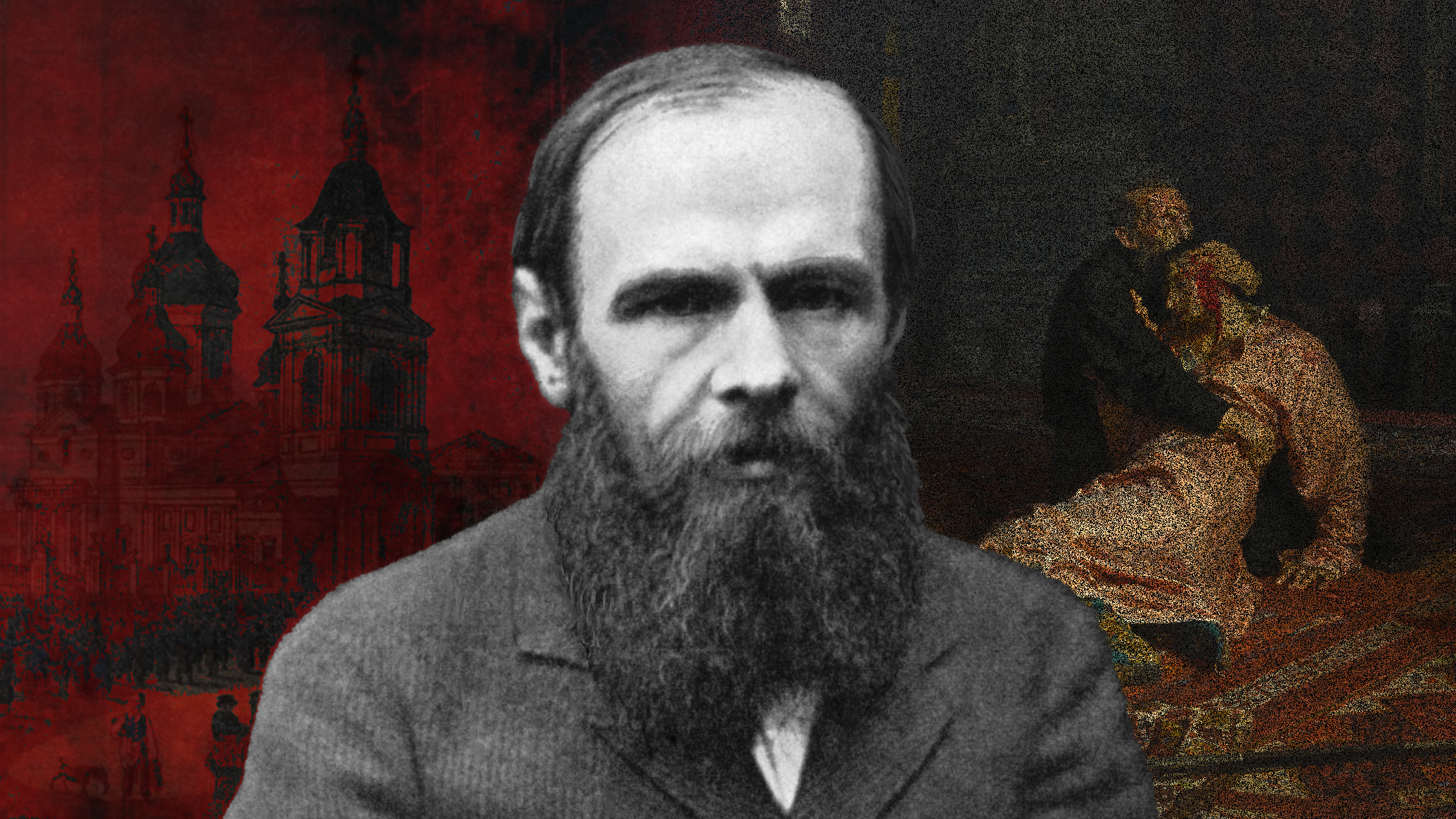

Dostoevsky’s Demons in the Modern World

Last week, I wrapped up a month-long reread of one of my favorite novels by the great Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky: Demons. I first read the novel back in 2023, and I will humbly admit that key details from the first 500 pages largely went over my head. However, the closing 160 or so pages had me white-knuckling the book, utterly consumed by the furious pace and unsettling scenes. What makes Demons such a perennially perplexing novel is its resistance to being pinned down. Like every enduring classic, it interlaces the political and cultural conflicts of its day with timeless dilemmas that have plagued humanity for millennia. Beyond the underground conspiracy, contentious liaisons, and a slew of Russian diminutives, lies a thorough examination of human psychology—that remains ever relevant in today’s increasingly nihilistic, apathetic society.

Fyodor the Psychologist

Writing within a canon that includes Pushkin, Gogol, and Tolstoy, Dostoevsky stands a head above most because of the psychological and philosophical insights he masterfully wove into his fictional works. From doomed dreamers to virginal women to inveterate gamblers—like himself—his stories portray a large swath of benevolent and malevolent archetypes in society. Often, the characters operate like mascots for particular ideologies, like the rationalist Ivan Karamazov in The Brothers Karamazov or the idealist Prince Myshkin in The Idiot, but other times he constructs enigmatic figures that elude any clear set of beliefs. Possibly his most intriguing, mystifying character is Nikolai Vsevolodovich Stavrogin from Demons, who I’ll return to in greater depth later on.

The Psychology of Dissent

Dostoevsky not only had a grasp of the psychology of individuals, but also a deep understanding of societal movements and the hive-mind that drives them. Opening in Part Three of Demons, he condemns and mocks those involved in aimless, rebellious movements:

“This scum, which exists in every society, rises to the surface in any transitional time, and not only has no goal, but has not even the inkling of an idea, and itself merely expresses anxiety and impatience with all its might. And yet this scum, without knowing it, almost always falls under the command of that small group of the “vanguard” which acts with a definite goal, and which directs all this rabble wherever it pleases, provided it does not consist of perfect idiots itself-which, incidentally, also happens.”

For centuries, civilization has quaked under the influence of powerful, bombastic leaders—both in positive and negative directions. These figureheads carry the force of a movement, and sometimes of an entire nation. They need no clear plan, goal, or evidence to support their claims, but merely charisma and alluring promises to compel impressionable populations to act in accordance with their aims. Dostoevsky develops this in microcosm within Demons, where a fivesome of radical socialists led by Pyotr Stepanovich Verkhovensky wreak havoc upon their town. In the story, Pyotr is no mastermind. He has no carefully devised scheme or prophetic vision; he is simply an agent of chaos, haphazardly inciting individuals to fulfill his demands.

What Dostoevsky saw in his own day from Herzen and Chernyshevsky-inspired radicals was amplified decades later by the Bolsheviks. Led by Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, independent movements consisting largely of laborers, peasants, and women activists were co-opted and incorporated into the Bolshevik cause. Like Pyotr, Lenin himself was rarely at the scene of the action, typically in exile or writing in Geneva. Instead, his insightful rhetoric spoke directly to the justified movements of dissent and harnessed their emotion into a unified cause, led by a select view—like the small vanguard Dostoevsky described above.

Today is no different. There are several immense socio-political movements in the U.S. and abroad that operate like hives, loyal to no end and easily swayed by the commands dictated by a select few. In Demons, Dostoevsky even satirizes these types of subservient followers who latch onto raving, charismatic leaders. He describes them as “little fanatics” who “simply cannot understand service to an idea otherwise than by merging it with the very person who, in their understanding, expresses this idea.”

And Dostoevsky knew where this innate psychological makeup of civilization led: destruction. The playbook is simple: prey on reasonable anger and dissent, organize the masses, profess a promising—realistic or not—solution, and convince them to upend the current system to construct a newer, ostensibly better one. As expressed earlier, these groups are often unified by emotions, not by a collective vision. Effective reform or any practical methods for achieving their goals are out the window. It’s always easier to destroy than to create. Movements typically prefer to tear down the current regime even before visions for a replacement have been considered, let alone articulated and evaluated.

Demons is often seen as prophetic of the successful Bolshevik revolution, but he had studied the aftermath of several historical events, such as the French Revolution and various fiery uprisings in his own lifetime; it didn’t take Nostradamus to predict where this cyclical behavior would take Mother Russia. It’s important to note that this rebellious behavior isn’t exclusive to Russia or humanity’s past—it’s even stronger today, fueled by influencers and leaders who can reach your ears 24/7.

Modern Nihilism

Bertha Wegmann, Despair (1886)

Out of all of Dostoevsky’s elaborate inventions, I could not name another as emblematic of today’s youthful generations as Nikolai Vsevolodovich Stavrogin. As the centerpiece of Demons, Nikolai is puzzling from the very start of the novel. Born into a wealthy, noble family, his father passes away in his youth, so his mother enlists the help of a former academic, Stepan Trofimovich Verkhovensky (yes, he’s the father of the revolutionary leader Pyotr), to raise her son. All goes according to plan for a while, until he returns and plays several shameful pranks on the townspeople, including mockingly pulling a gentleman by his nose in public. It’s all swiftly forgiven and written off as a temporary state of mania brought on by brain fever, but that’s not the end of it. Years later, he returns from time spent in Switzerland and Petersburg, only to have disgraced himself by marrying a lame woman. Of course, that’s not all. As the novel unfolds, we learn of a whole host of frivolous affairs, revolutionary involvement, and a particularly vile act censored in the novel’s original publication. Despite his idiosyncrasies and fictionalized persona, his unsettling speech and apathetic actions make him a relevant figure to analyze.

Today’s culture possesses a new strand of nihilism. Rather than rejecting meaning outright, it dances around the question and mocks it entirely. Religion, family, authority, and definitive values themselves are rejected. They are seen as relics of outdated, hypocritical generations. The youth are exposed to the failures of traditional values and institutions like never before. Their social media feeds are flooded with concurrent wars, vitriolic political division, and black comedy memes that don’t just step on the line of insensitive subjects, but fearlessly travel deep into the abyss. The proliferation of trolls and edgelords, who intentionally create extreme, insensitive posts, has established a culture of apathy across the internet. Everything is a joke and worthy of being mocked. Nothing is serious. It’s this lack of seriousness that bleeds into offline personalities and behavior as well. Daily interactions or relationships are treated like one big meme or just another inconsequential “shitpost.”

Regarding relationships, millions of youth struggle to navigate intimate connections in a landscape littered with licentiousness, dating apps, and widespread pornography use. According to data from the National Opinion Research Center’s General Social Survey, American wives were nearly 40 percent more likely to cheat in 2010 than in 1990. This is a statistic we can only assume has climbed rapidly with the emergence of social media and apps like Tinder, which tempt millions of supposedly committed individuals with hot, new opportunities just down the street. This willingness to disregard the feelings of one’s partner and devalue the notion of commitment shows an accelerating erosion of values in modern culture. Like the frequent affairs of Nikolai Stavrogin in the novel, who seemed to get around with just about everyone, men today flippantly drift from hookup to hookup with a glaring lack of sincerity—but men aren’t the only ones. As if in competition with the odious behavior of men, women are increasingly fielding larger pools of partners and taking full advantage of the eroding stigma associated with possessing a high number of sexual partners.

In totality, the youth are progressively becoming a valueless, unhappy, pleasure-seeking generation. Similar to Nikolai, Gen Z finds itself lukewarm, indifferent to every sensation or purpose around them. Their lack of belief and values operates like a black hole, extracting seriousness, joy, and meaning from their lives. In the novel and in life, moral conventions and long-established values—honor, truth, fidelity—serve as the foundation of society. They root civilization so that it can withstand violence, terror, and madness. If society becomes de-rooted, our humanity and dignity will be quick to collapse. The decoupling of the youth from these longstanding, cherished values will inevitably be their demise. Much like the nihilistic Ippolit in Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, these pernicious ideologies always create terminal cases.

We Need an Exorcism

We exist in an increasing dissociative wasteland of conscienceless profligates, rampant promiscuity, and insincere leaders that join pre-existing cyclical corruption rather than dismantle it. Unfortunately, authors are typically better are illuminating the errs of society and rarely, if ever, proffer a coherent solution.

Dostoevsky’s attempts to counteract this spiritual terrorism are embodied by Ivan Shatov, a repentant former revolutionary, and Stepan Trofimovich, a foolish romantic. Toward the end of the novel, Shatov rejects the rebirth-through-destruction ideologies of Shigalyov and returns to Christian faith as a place of refuge—much like Dostoevsky himself. On the other hand, Stepan takes a romantic approach, proudly endorsing the pursuit of transcendent ideals:

“My friends, all, all of you: long live the Great Thought! The eternal, immeasurable Thought! For every man, whoever he is, it is necessary to bow before that which is the Great Thought.”

Of course, the flaw of both characters is that they are presented as raving fools who ultimately meet tragic ends. By consistently mocking his noble characters and giving them devastating fates, Dostoevsky seems to hint at the legitimacy of skepticism toward his own values. You sympathize with these benevolent characters for their virtue and faith, yet you can’t help but question whether they should be trusted.

Henrik Karlsson eloquently articulates this recurring feature of Dostoevsky’s heroes, who, despite pronouncing honorable ideas in long-winded, philosophical monologues, are simultaneously mocked and revealed to be ineffectual dreamers:

“Compromising the characters forces the reader to stand alone, to borrow Kirkegaard’s phrase. Since there is no safe authority that you can submit to in Dostoevsky’s books, it is up to you to meet these hurting, strange voices with compassion, critical thinking, and curiosity; you have to evaluate if anything they say is valuable and true and applies to your life.”

So, do we choose the honorable death of the Kierkegaardian Knight of Faith? Or do we dismiss the impractical dreamers? These are the sorts of existential questions that arise out of Dostoevsky’s novels and philosophical inquiry. As one would expect, there are no good answers, only personal ones.

Albert Camus instructed us to adopt the Sisyphean absurdist approach, while Sartre advocated for the individual to create their self-derived meaning through action. Whatever we decide, we must avoid the absence of purpose and virtue. Nihilism, or a Stavroginian approach, is a white flag to existence—a surrender to its absurdity. A submission we must not offer.