Destruction as Salvation: László Krasznahorkai

Since the dawn of civilization, and even reaching back into our deepest origins, humanity has endured war, chaos, and suffering. Generation after generation has succumbed to cruelty and an insatiable thirst for power. Cities have burned, regimes have collapsed, and entire groups have been exterminated. In the totality of human history, peace has remained an evanescent abstraction clung to by the destitute with mouths agape, reminiscent of Munch's The Scream—feverishly searching for salvation in the wake of utter destruction. What do we make of such pervasive decay and disaster? How are we to make sense of a senseless world filled with devastation? And is there hope? In his melancholic four-part series of novels—Sátántangó, The Melancholy of Resistance, War & War, and Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming—known as the Apocalypse Quartet, Hungarian author László Krasznahorkai explores these harrowing questions.

You can find my video companion to the essay here.

The Germination of Desolation

The source material for Krasznahorkai’s abstruse and maniacal works originates from his dismal childhood. Krasznahorkai was born in 1954 in the small town of Gyula, which was located in the Hungarian People's Republic—two years before the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. The Hungarian People's Republic was a one-party socialist state, which worked in close conjunction with Stalin’s regime, until its dissolution in 1989 as part of a cascade of collapsing Communist states towards the end of the 20th century.

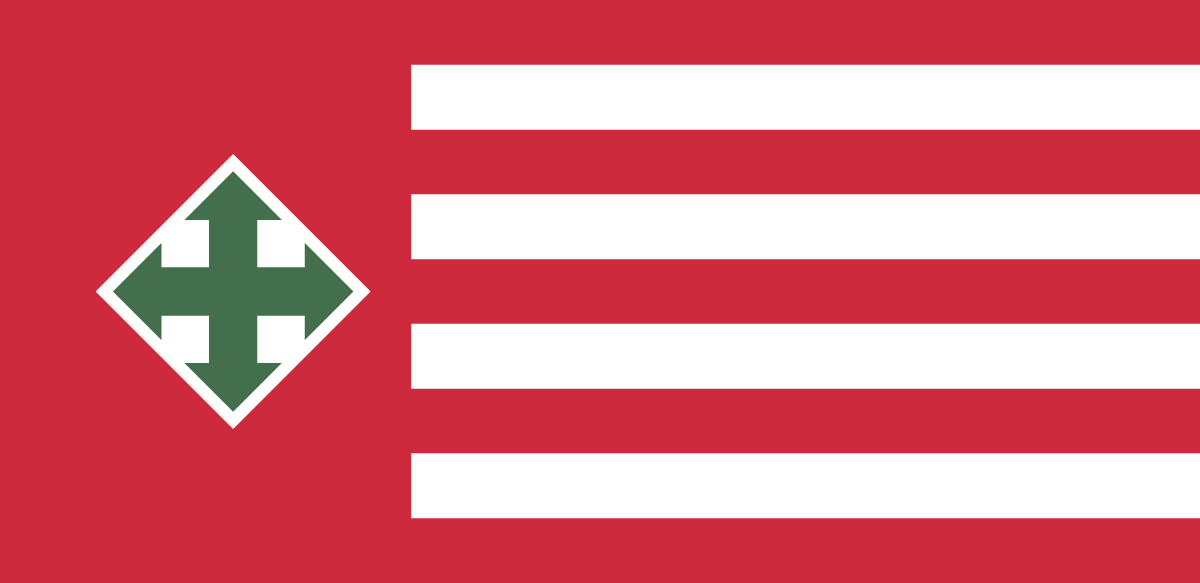

Flag of the Arrow Cross Party

Prior to its formation in 1949, Hungary participated in a litany of violent human atrocities and war crimes. As part of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary, Hungarians were aligned with the Central Powers during WWI, which cost the lives of nearly 530,000 Hungarian soldiers and civilians; however, the country’s future became more sinister with the emergence of the second World War. Rooted in their alliance with Hitler’s Nazi Germany, the Hungarian government enacted various anti-Semitic laws and deported nearly half a million Jews over the course of the war. One of the darker moments of this period was the five-month stint of control by the Arrow Cross Party. Under the leadership of Ferenc Szálasi, the far-right Hungarian ultranationalist party murdered thousands of civilians, many of whom were shot into the Danube River. In order to save bullets, soldiers would wire three men together by the river, shoot the outside men and let the weight of their bodies drown the middle man. Unfortunately, these grim times only got worse.

Hungarians toiled through Communism, attempting to flee whenever the chance presented itself—including the escape of 240,000 during the 1956 revolution. Witnessing the terror around him, Krasznahorkai fled Gyula at the age of 18 and planned to live amongst the downtrodden after reading the sorrowful works of Russian writers like Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy. He explained his reasoning in an interview:

“I thought I should go and live amongst the poorest and most oppressed because under communism, of course, they still oppressed the same people who have always been oppressed under all systems.” (Interview from Louisiana Literature)

In Krasznahorkai’s eyes, all of this death and destruction has left multiple generations of Hungarians with no memory of a once prosperous empire, but only the harsh reality of a shameful, diseased, decayed country plagued by suffering, clinging to a chimera of hope.

The Apocalypse is Already Here

Within each of his four disturbing, experimental works, Krasznahorkai yanks us into dystopian worlds marked by varying degrees of environmental decay and societal collapse. Although each contains a distinct, jarring story, the motif that runs like a river connecting them all is the presence of the apocalypse.

Now it doesn’t take a genius to convey the apocalyptic sentiments in the “Apocalypse Quartet”, but it would be a mistake to describe it in any other way. A fear, and at times yearning, for the end of days lives at the heart of each of these fictionalized worlds. Much like ourselves, the characters find themselves drifting through a muck of misery, helpless to make sense of the societal corrosion and death they’re enwrapped in. Krasznahorkai uses vivid description and powerful literary devices to convey the way in which the city wreaks and has gone to rack and ruin in The Melancholy of Resistance. Instead of classic depictions of floods, hellfire, and demons, the apocalypse for Krasznahorkai is purely manmade. Rumors of uncertainty and final judgment swirl in a frantic tumult, permeated by fear, “this epidemic of fear was not born out of some genuine, daily increasing certainty of disaster but of an infection of the imagination whose susceptibility to its own terrors might eventually lead to an actual catastrophe.” In the other novels, the imminent arrival of total collapse is shown more subtly through venomous corruption and duplicitous ‘saviors’. Each town survives through their current damnation due to the presence of millenarianism—a conviction that the Last Judgement is fast approaching and hope lies on the other side.

In The Melancholy of Resistance, the manipulative opportunist Mrs. Eszter possesses this same millenarian perspective through pragmatism rather than religion or idealism. The story is propelled by the arrival of a forbidding circus into a disorderly town, rotting and stewing in degeneracy. Lusting for power, she sees this teetering on the edge of anarchy as a chance to wipe away the decay and sins of the past, preparing a new path “leading to something new, something of infinite promise”. Through the exploitation of her husband’s reputation and her witty slogan of “A Tidy Yard, an Orderly House”, she positions the ominous circus as a scapegoat and preys on the paranoia of the town in order to push them into a state of anarchy. I can't help but draw parallels to the fear-mongering propagated by modern-day politicians and media outlets.

Whether the answer comes in the form of scripture or a charismatic leader, Krasznahorkai sees Hungarians as starving for an answer to their eternal damnation. Surrounded by sin, death, and a diseased society, they are ready and willing to submit to any potential savior.

Seeking External Salvation

In an existence that contains pain and suffering and that inevitably ends in death, the concept of salvation always remains an abstraction—Krasznahorkai makes this clear. In War & War, György Korin, a suicidal archivist, discovers an arcane manuscript that he believes contains a sacred message. Desperately scrambling to New York on his “road to eternal truth”, he works to slowly upload this manuscript to the internet in order to preserve its message for eternity, only for his server to erase it due to insufficient funds and for the document to contain “no Way Out”. Other characters aren't so lucky either.

Within The Melancholy of Resistance, Valuska, an ebullient dreamer, finds salvation in the expansive Cosmos before he later finds himself irrevocably involved in a night of madness. Mr. Eszter, a famous public figure and husband to the wicked Mrs. Eszter, experiences the same disenchantment when he discovers a theory for perfection in musical pitch until it’s all revealed to be a miscalculation. By the end of the novel, both characters find themselves utterly disillusioned, unlike those in Sátántangó who are pulled deeper and deeper into a scheme by the cunning Irimiás. His debut, Sátántangó, features a small village in Hungary full of amoral, licentious characters who fail to see themselves as the makers of their own bleak existence. They persist in a state of denial and ignorantly seek deliverance in a man they know is likely to deceive them. And Krasznahorkai’s final act of the quartet isn’t too different. Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming brings us closer to modern day featuring a fictionalized Hungarian town full of corruption and decadence. Eager to believe what they want to, the downtrodden community places its hope in the idea of a man rather than the reality of who he truly is.

The flaw of each idealistic or hopeful character is their reluctance to recognize that their dreams were always fictions. They never contained a kernel of reality or evidentiary grounding. Krasznahorkai drives this point home strongest in Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming, where the return of Baron Béla Wenckheim to his hometown resembles that of a second coming of Christ. He’s thought to bring with him wealth, order, and love that will reinvigorate the citizens and rebuild the town’s glory. Meanwhile, a slew of bad actors seek to manipulate or exploit the Baron, who himself is a profligate fleeing gambling debts in Argentina. The desperation for salvation temporarily suspends morality, therefore introducing a state of anarchy that welcomes wicked creatures like Mrs. Eszter.

Krasznahorkai uses these various figures to mock the irrational idealism that professes things will get better when reality shows otherwise. But it’s this conception of hope and salvation that allows humanity to withstand such horrid conditions. It offers an attempt (although weak) to make sense of suffering and attach meaning to it. It also allows civilization to shift the blame onto nature or fate rather than themselves. We’d rather choose foolish bliss than surrender to nihilism.

Protesters during the Hungary Revolution of 1956

Instead of recognizing themselves as the creators of their own nightmare, human beings prefer to exist in a “convenient fog” and absolve themselves of any blame for the current state of matters. Irimiás, the prophetic con man, criticizes the sinful people of the town in Sátántangó and their self-pitying, learned helplessness: “Your helplessness is culpable, your cowardice culpable, culpable, ladies and gentlemen! Because— and mark this well!— it is not only other people one can ruin, but one-self!” It’s this cowardice that Krasznahorkai aggressively ridicules through an anonymous, vituperative article in Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming, which condemns the “diseased” Hungarian soul. This incendiary manifesto recalls the pusillanimity of the nation’s past, suggesting that:

“Whoever is Hungarian continually postpones his present, exchanging it for a future which will never arrive, whereas he has neither a present nor future, because he has renounced the present for the sake of the future, a future which is not a true future.”

We Were Always Doomed

In his interview with Louisiana Literature, Krasznahorkai makes his philosophy of the world blatantly clear: “The apocalypse is what we are living in.” Blunt, direct, but possibly true. Perhaps the ominous figure of Mastemann, a reappearing gnostic in the cryptic manuscript, in War & War is right when he says, “THE SPIRIT OF HUMANITY IS THE SPIRIT OF WAR". Neither the Age of Enlightenment, widespread democratization, nor the rapid technological advancement of the world has been able to stop humanity from tearing itself apart. The fumes of hatred continue to stoke the ever-burning flames of power, evil, and oppression. Mr. Eszter operates as the mouthpiece for Krasznahorkai when he adamantly asserts this condemnation of mankind to Valuska:

“there will be neither apocalypse nor last judgement…such things would serve no purpose since the world will quite happily fall apart by itself and go to wrack and ruin so that everything may begin again, and so proceed ad infinitum.”

It’s the illusion of hope that is both our greatest flaw and greatest lifeline as a species. Surrounded by despair and amoral industrialization, Korin dedicates the last months of his life to making sense of an inherently senseless text. The manuscript features a cast of four men who repeatedly fall into a pattern of settlement, war, and exodus, leaving Korin baffled. Refusing to face his own temporality and meaninglessness, he leans on elaborate interpretation to discover some form of sacred truth like a religious zealot. Instead of choosing to “breathe the dizzying air of freedom”, he regresses into a state of fear, pulling the sheepskin back over his eyes to avoid staring down into the sickening abyss of his inevitable demise. In other words, he is like us. We look away from the immemorial concatenation of war that shapes human history and reach for the ghost of peace that has never crossed into the natural world. Irimiás attempts to convince us to let go of our empty ideals:

"That's precisely why I say we are trapped forever. We're properly doomed. It's best not to try either, best not believe your eyes. It's a trap, Petrina. And we fall into it every time. We think we're breaking free but all we're doing is readjusting the locks. We're trapped, end of story."

A Failure To Answer The Unanswerable

“I've long understood there is zero difference between me and a bug, or a bug and a river, or a river and a voice shouting above it. There's no sense or meaning in anything. It's nothing but a network of dependency under enormous fluctuating pressures. It's only our imaginations, not our senses, that continually confront us with failure and the false belief that we can raise ourselves by our own bootstraps from the miserable pulp of decay. There's no escaping that, stupid.” - Sátántangó

In his promotion of the fourth novel, Krasznahorkai claimed that this work was meant to be the culmination of one single project. So along with other readers of the first three novels in the quartet, I expected Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming to provide some sort of answer or escape from the abhorrent madness we find ourselves in. Alas, the novel only added more kerosene and gleefully lit the flame.

To Krasznahorkai’s defense, in order to construct a world that provides meaning and achieves peace it would have to be truly be a fictionalized world in every sense of the word. It would not be a world that we could believe in or draw a correlation to with our own. We struggle to attach peace and love to existence because all we’ve known is chaos and hatred. Instead, Krasznahorkai’s desire is simply to convey what he sees as the intrinsic thread tying all of humanity together: eternal hope. In his own words:

“I am in fact trying to give hope, especially with my last book - Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming. The end of things, disaster, death - this is due to the fact that at the end of human life and nature is always the death of the individual. […] Without that, you can’t tell a story about a situation, especially not about the state of the world. It’s simply a part of it.”

Unconventional Storytelling

I’d be remiss if I didn’t address the elephant in the room regarding Krasznahorkai’s writing style—namely, the chapter-long sentences. This idiosyncratic flavor to his prose will certainly amplify the reading experience for some, while it will make others cast their copy into the flames.

Writer James Wood skillfully addresses this in his New Yorker article on László Krasznahorkai, referencing various fiction writers who have experimented with sentence structure, such as Roberto Bolaño, David Foster Wallace, and others. Wood dissects the usage of this style, comparing it to a “lunatic scorpion trying to sting itself” in the way that it stretches and retracts back onto itself. I will leave technical literary analysis to the experts, but I will share my personal experience along with Krasznahorkai’s own words on the origin of his works.

For me, his serpentine, deductive, seemingly never-ending sentences create a stream of consciousness that gushes like a whitewater river rather than a tranquil stream. In the same interview referenced earlier, he mentions how he wrote the first draft of Sátántangó in his mind as he worked on a dairy farm. Reciting the story over and over in his mind before ever transferring it to paper, one can imagine the kind of continuous style that emerges from such a process. It’s also worth considering how music shaped his life and writing style. He grew up an avid musician as an adolescent, but turned to literature because “words offer not only conceptual, but also musical opportunities for expression”. His prose carries an unbroken rhythm much like a choreographed dance or symphony. For this reason, what is sacrificed in grammatical convention is exchanged for linguistic elements that reach beyond the page.

My “Final Judgement”

After reading each book in the quartet consecutively and stewing in Krasznahorkai’s chaotic world, I was equally thrilled and unsatisfied. Each work offers a perplexing plot line and an experimental—personally delightful— writing style, but I’m not sure how much is gained by treating them as a quartet. In my mind, they share a theme, but they don’t necessarily build upon each other in a way that requires one to read them all to understand the central message.

Also, I feel that Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming is a book that could be skipped for most readers. It is nearly twice the length of the other three books, but contains much of the same idea repackaged. There are some nuances to it and sections that express sheer brilliance, but by and large it was the weakest of the bunch. Although if you love Krasznahorkai’s style, then it’s worth getting around to. In my opinion, the other three novels—Sátántangó, The Melancholy of Resistance, and War & War—pose profound societal questions through creative storytelling, making each one worthy of a reread.

Krasznahorkai is clearly one of the more experimental, riveting writers emerging out of the Postmodern tradition. Despite our longing for answers to chaos and destruction, his works are emblematic of reality and not what we wish it to be. Through his disturbing stories, he has cast a light on the afflictions of humanity, and it is our duty not to sit idly as his characters have but to seek ways to resist them.

Works Discussed:

Sátántangó translated by George Szirtes

The Melancholy of Resistance translated by George Szirtes

War & War translated by George Szirtes

Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming translated by Ottilie Mulzet