Parodies of Russian Oddities & Political Machinations

Reviewed:

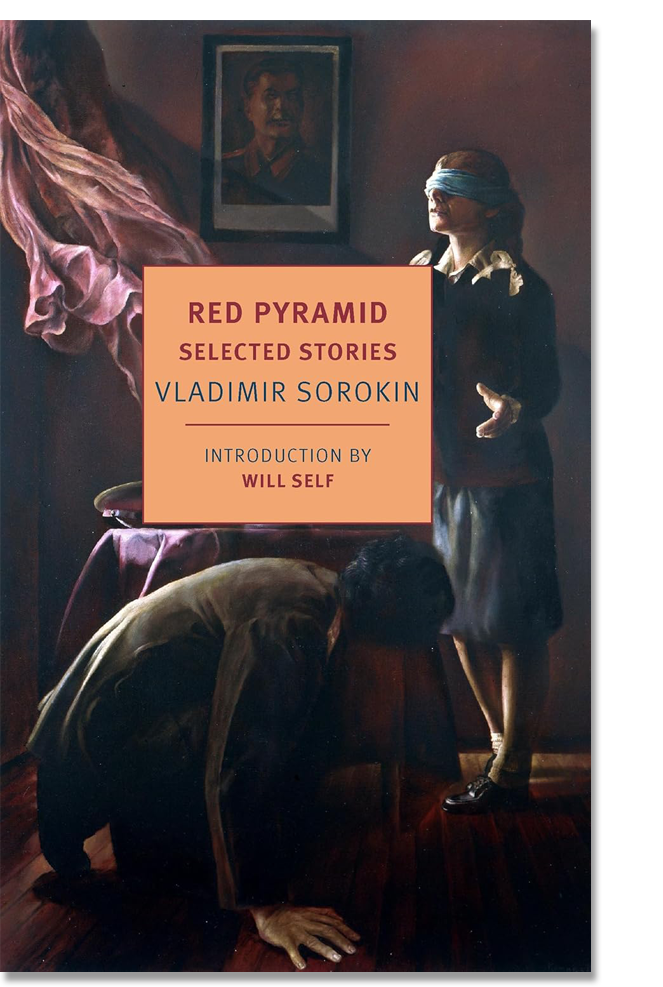

by Vladimir Sorokin

Translated by Max Lawton

NYRB Classics, 320 pp., $19.95 (paper)

Publication Date: 2/27/24

Like a car crash one can't look away from, Red Pyramid delivers a puzzling collection of stories by the Russian émigré Vladimir Sorokin. Over the past four decades, Sorokin has written a steady stream of grotesque, inventive works that stretch classical Russian prose into pure absurdity. Bolstered by curious English-speaking readers, Sorokin has secured a new cult following in recent years; this collection showcases his ability to shock, provoke, and disgust.

The selected stories range from erotic encounters to reports set in Dachau to nuclear warheads transformed into refined sugar, each beginning with unmistakable Soviet realism before abruptly shifting into surrealist spectacle. The standout story “Nastya” follows a sixteen-year-old girl who is prepared, cooked, and served as the main dish at a grandiose feast. As the attendees carefully select their desired cuts, the conversation centers on Nietzschean philosophy and the consequences of a society rooted in such ideals: “Every society that kicks the fallen when they're down ends up falling itself” (p. 86). Another notable story is “Horse Soup,” in which a former criminal solicits a young woman to eat in front of him while he convulses with pleasure. In the title story, a man named Yuri converses with an odd gentleman at a train stop who tells him that Lenin “called forth the pyramid of the red road” (p. 254), before Yuri later witnesses the immensity of the pyramid during a fatal heart attack.

Sorokin’s frequent use of fecal symbolism is sure to unsettle new readers, but once understood, it emerges as a central element of his enterprise. From its inception, the Soviet Union—and Russia to this day—has aggressively promulgated nationalism and state-endorsed rhetoric. In stories like "Obelisk," Sorokin portrays party slogans and the glorification of the past as ideological excrement, force-fed to generation after generation. Despite his undeniable wit and amusing narratives, his thematic depth often leads into an abyss rather than a path towards enlightenment. This can be seen in “White Square,” which follows a panel of guests on a TV show, each sharing a different analogical view of Russia. The story feels guided toward a specific message, but like many of the others, it flies off the rails into obscurity. Although it may be Sorokin’s intention to leave interpretation and societal examination to his readers, greater clarity would likely improve reception among an otherwise nonplussed audience.

Rooted in cultural critique and surrealism, Sorokin thrills in Red Pyramid, while missing more than he lands. His prose knows no bounds, but when left uncontrolled, it descends into ambiguity at a pace too furious to track. Readers familiar with his style will find themselves right at home in his maniacal crafted stories, but his enigmatic endings and experimental features will keep him secluded from a mainstream audience. For that reason, Sorokin remains one of Russia’s best-kept secrets and a doomed recommendation for unsuspecting friends.