Satirical Surrealism in Resurrected Medieval Russia

Reviewed:

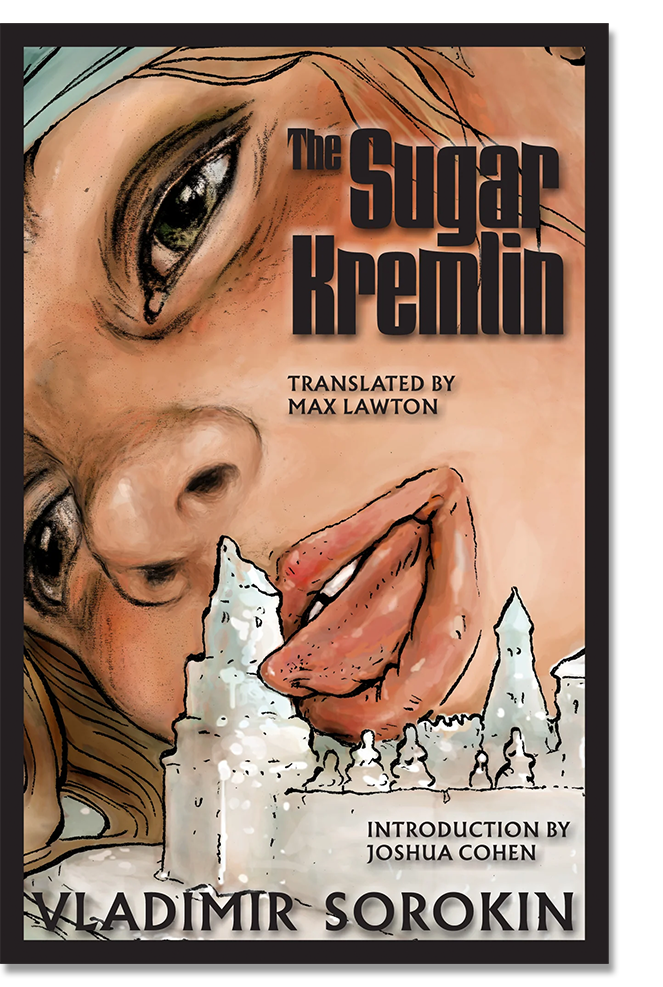

by Vladimir Sorokin

Translated by Max Lawton

Dalkey Archive Press, 256 pp., $18.95 (paper)

Publication Date: 9/30/25

Equally decadent and delirious, The Sugar Kremlin depicts an eerie dystopia plagued by draconian conventions and abject machinations. In a continuation of Sorokin’s Day of the Oprichnik, the oppressive, virile goons are back, wreaking havoc across resurrected medieval Russia. Told through a series of perverse, polyphonic vignettes, the novel blends grim visions of a society caught in cyclical decline.

Sorokin structures the novel across fifteen distinct chapters, each portraying a defining feature of despotic Moscovia, linked by the recurring presence of sugar replicas of the Moscow Kremlin. From the implacable interrogator Sevastyanov to the daft, effervescent Marfusha, each citizen finds themselves mollified by the familiar, sticky sweetness of the Kremlin. Despite his avoidance of direct political commentary, Sorokin cleverly mocks modernized totalitarian tools of state policing and censorship, and includes an allusion to former President Boris Yeltsin as the “Three Fingered Foe.” As eccentric characters and mediocre laborers find their lives inevitably encroached upon by the sovereign and his minions, it becomes clear that persisting through generations of political turnover are queues, erotic desire, and the unchecked abuse of power by the state. Old Bolshevism remains alive and well in this society—the belief in a perpetual war against “internal enemies” and an elusive, collective mission to bring about utopia:

“There y’go, Granddaughter, if every schoolchild molded a single brick out of our native clay, then the Sovereign would finish the wall immediately and a happy life would begin in Russia."

As always, Sorokin’s quirky style introduces all sorts of shock, awe, and intrigue that work in sprints but can occasionally dull over the long haul. Early chapters feature sharp, clear subtext and imaginative elements that deliver both poetic and narrative punch, such as “The Poker.” In this chapter, an imprisoned dissident named Smirnov is accused of writing a seditious story depicting a dispassionate Russian who mindlessly fulfills his role in society, even to the point of serving the secret order—personifying a replaceable poker whose only function is to stoke the flames of the regime. After enduring futuristic methods of torture, a torrent of names spills from Smirnov’s mouth as he becomes the very instrument of the state he once derided. On the level of language, Max Lawton’s brilliant translation retains Sorokin’s satirical humor, such as the mention of the “interYes” (in reference to the Russian word for no—нет), and his skillful choice of words helps give fluidity to the frenetic dialogue.

With the passing of time, Sorokin’s disturbing creations become less fictional and more prophetic. His fears of a medieval-like totalitarian resurgence inch closer to reality, even in nations beyond Russia, and his infusion of Chinese language and culture reflects geopolitical shifts that draw neighboring allies closer in the modern world. For now, The Sugar Kremlin remains an extravagant circus of peculiar tales and comical caricatures that express the inexorable grasp of all forms of sovereignty.