Oddballs & Delightful Oddities

Reviewed:

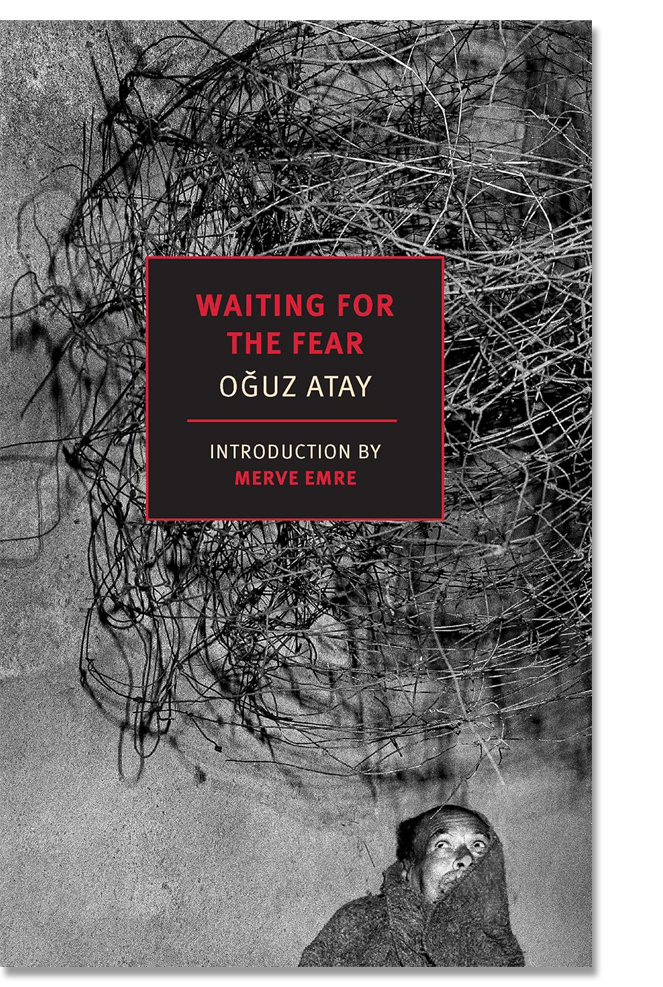

by Oğuz Atay

Translated by Ralph Hubbell

NYRB Classics, 240 pp., $16.95 (paper)

Publication Date: 10/22/24

Previously untranslated and unknown to an English audience, Atay’s Waiting for the Fear makes a boisterous statement with eight eccentric and highly amusing stories. While each story stands alone with its own jarring plot, psychological strain and a self-critical narrative voice permeate the entire collection. Through his depiction of a misunderstood vagrant, paranoid recluse, mourning son, and other bizarre personas, Atay constructs a world full of oddities and complexities while showcasing his talent for effective storytelling.

The collection begins with the curious tale “Man in a White Overcoat”, which follows a mute beggar carried along by the vicissitudes of the day. Repeatedly misinterpreted by strangers, he wanders around the town square in his newly acquired white overcoat, attracting attention that opportunistic vendors leverage to sell their garments. Pushed along by chance, he travels on a train with “all the people who were tired like him, and dirty like him, and indifferent, just like him, to the world they'd been forced to live in,” until he arrives at a beach, walks into the water, and drowns. This desire to resist random occurrence and enact control over one’s own life is a frustration that plagues many narrators in this collection, such as the manic, overthinking protagonist in the title story “Waiting for the Fear”. Paranoiac and anxious, the narrator’s innate unease becomes heightened when he is greeted with an envelope containing a threatening, cryptic message in a secret language. Unable to find relief through his usual "which meant”s and comforting explanations, he spirals into delirium and self-contempt for his own ineptitude. However, after his fear is assuaged, he finds the return to his predictable life uninspiring: “At least the time I'd spent at home waiting in fear, or waiting for the fear, mattered, it had a future. And the time I spent prior to receiving the letter also seemed more valuable now.”

One of the standout stories is “The Forgotten”, which pulls readers into the mind of a woman grieving her former lover’s suicide. As she cleans out the attic, stumbling upon old relics and envisioning the body of her deceased partner, she struggles to accept the reality of it: “No, he isn't really dead; if he was, I couldn't have gone on living. He knew that.” (pg. 25) Her reluctance to accept the past and inability to relieve herself of her own perceived guilt — “Why didn't I call to him? I suppose I just never had the chance; something always came,” (pg. 16) — makes a somber impression on the hearts of readers. Atay revisits a similar emotional tone in “Letter To My Father”, where a son laments his ambivalent feelings toward his father and fears his growing resemblance to him.

Despite his consistently eloquent prose, Atay misses the mark with a few stories in this collection, particularly due to stylistic or structural choices. “A Letter” presents a sporadic telling of events from the writer of an unsent letter to an unspecified recipient. “Not Yes Not No” contains moments of comedic commentary and ideas, but is riddled with constant interjections that make the story frustrating to read. “The Wooden Horse” is a promising story with a rebellious contrarian, but it likely becomes more compelling with additional reads.

As one of the most revered writers in Turkish literature, Atay delivers not only arresting stories full of quirky characters and memorable storylines but does so with a distinct voice and vivacious language.